Comprehensive Guide to Well Pump Repair Techniques

Overview and Outline: Why Well Pump Repair Matters

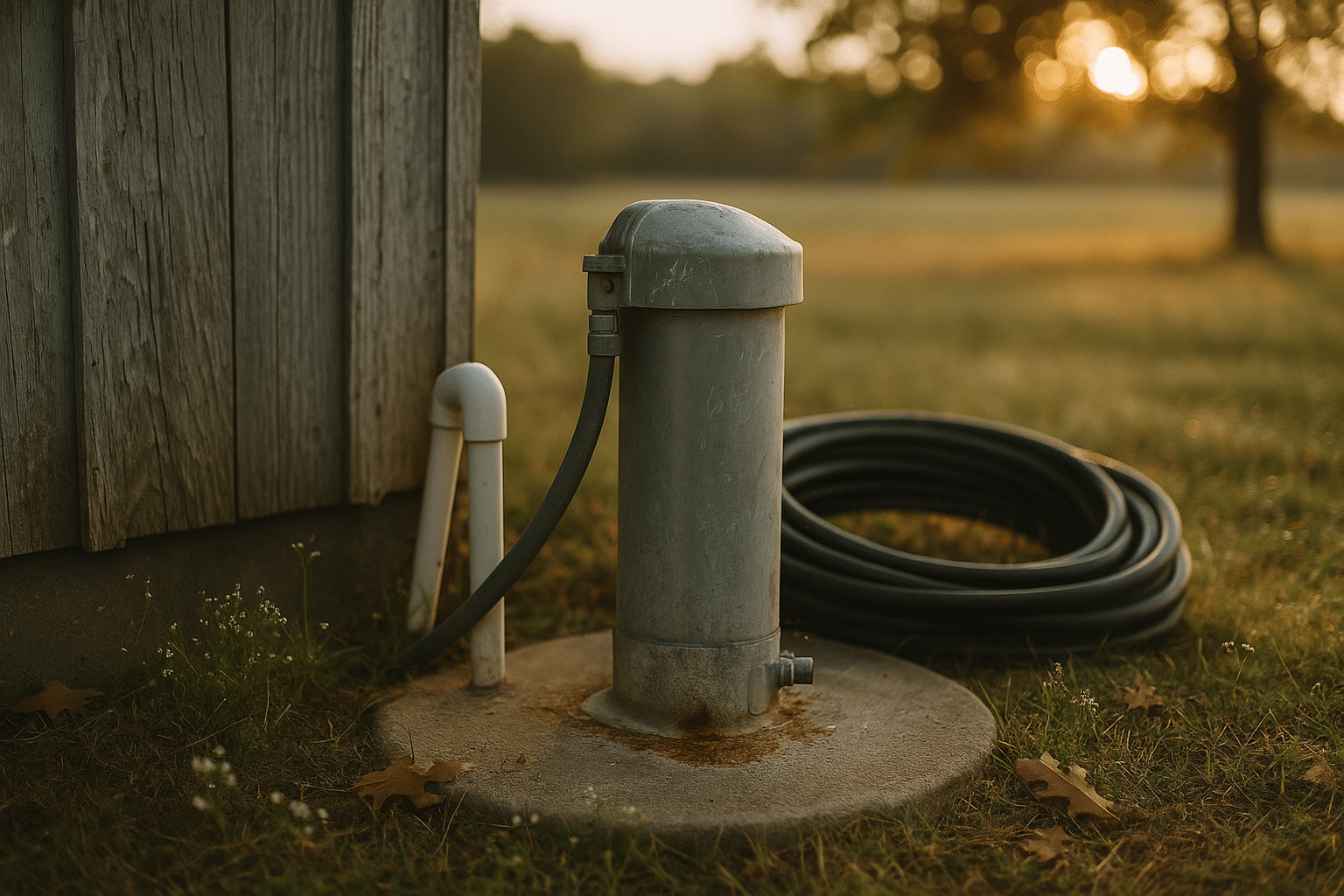

A dependable well pump turns groundwater into everyday comfort—clean dishes, hot showers, and a garden that doesn’t wilt by noon. When the system falters, however, you feel it immediately. Unstable pressure, short cycling, or a silent faucet can disrupt routines, waste energy, and risk equipment damage. This guide brings clarity to three pillars of care—maintenance, troubleshooting, and installation—so you can protect your investment, preserve water quality, and make informed choices about upgrades. Residential pumps often run for 8–15 years when sized and maintained correctly, but harsh water, high duty cycles, and neglected tanks can shorten that span. The goal here is not to turn every reader into a technician; it’s to equip you with structured steps, safety awareness, and practical reference points you can use at the right moment.

Before we dive in, here’s the roadmap for what follows:

– Maintenance: Scheduled tasks, water-quality checks, and how to keep motors, tanks, and controls in good condition.

– Troubleshooting: A structured flow—from “no water” to “low pressure” to “short cycling”—with the checks that isolate root causes.

– Installation: Planning, sizing for flow and head, safe wiring, sanitary well-head practices, and pressure tank matching.

– Optimization: Ways to reduce energy use, stabilize pressure, and extend lifespan through thoughtful upgrades and habits.

– Decision points: When DIY is reasonable, when to pause, and when a licensed professional should be your next call.

We’ll compare common system types—jet versus submersible pumps, steel versus polyethylene drop piping, and constant versus traditional pressure setups—so you understand the trade-offs. You’ll also learn how routine tests (such as checking a tank’s air charge or capturing motor amperage) turn guesswork into evidence. By the end, you’ll have a checklist-driven playbook that preserves reliability and helps you respond calmly when something changes—because a steady water supply is less about luck and more about habits and good information.

Preventive Maintenance for Long-Lived Well Pumps

Preventive maintenance is the quiet engine of reliability. It reduces energy waste, prevents avoidable failures, and keeps water quality where it should be. A well pump system is a team: the pump moves water, the pressure tank dampens cycling, and the switch governs on/off thresholds. When any one part drifts out of spec, the rest work harder. Consistent checkups catch drift early, keep parts aligned, and extend overall life. Think in rhythms—monthly glances, seasonal inspections, and annual deep dives—so you never lose track.

Monthly and seasonal tasks focus on easy signals. Walk the line from well head to pressure tank: listen for chattering at the switch, feel for unusual vibrations on piping, and look for damp soil that hints at a leak. Check the pressure gauge while someone opens and closes a faucet. Smooth swings between, say, 30/50 or 40/60 psi indicate healthy cycling; wild swings or rapid clicking point to a tank or switch issue. In winter climates, confirm insulation around the well cap and exposed lines is intact, and that vents on the cap remain clear so the casing breathes without inviting pests.

Annually, give the system a full physical:

– Power down at the breaker, then drain the system. Measure the pressure tank’s air charge with a tire gauge; set it 2 psi below the switch cut-in (e.g., 28 psi for a 30/50 setup).

– Test water for sediment, hardness, iron, and bacteria. High sediment accelerates wear, and iron can foul fixtures and reduce flow; address with appropriate filtration or treatment.

– Replace or clean filters as recommended by their micron rating and water conditions; a clogged cartridge raises backpressure and forces the pump to work harder.

– Inspect wire splices in accessible locations for corrosion, and verify conduit connections remain watertight.

– Review amperage during a controlled run. Compare to the motor’s nameplate draw; rising current at the same flow may suggest bearing wear or partial blockage.

Two comparisons help frame decisions. Submersible pumps generally run quieter and more efficiently than shallow-well jet pumps, especially for deeper water tables, but retrieval requires lifting the drop pipe. Jet pumps reside at the surface, making service easier, yet they are more sensitive to suction-side leaks and priming. For drop pipe, polyethylene is flexible and corrosion-resistant, while steel offers rigidity and durability under high temperatures but adds weight and can corrode in aggressive water. Choose based on well depth, water chemistry, and handling preferences. Finally, keep a maintenance log—dates, readings, and parts changed—because the most valuable diagnostic tool is a clear history that reveals trends long before failure arrives.

Troubleshooting: From Symptoms to Root Cause

When something changes—no water, weak pressure, or fast cycling—slow down and follow a structured path. Start with safety: switch off power at the breaker and verify with a non-contact tester. Reset only when needed to test a hypothesis. The objective is to isolate where the issue lives: power supply, control circuit, pressure tank, or the hydraulic path from aquifer to faucet. Listening matters. A pump humming continuously without pressure gain hints at a leak, blockage, or a failing impeller. A silent system may be an electrical interruption or a stuck pressure switch.

No water at the tap? Begin with these checks:

– Electrical continuity: Confirm the breaker, fuses, and any GFCI/RCD devices. Inspect pressure switch contacts; pitted points can stick or fail to close.

– Pressure tank reading: If the gauge sits below cut-in and nothing starts, the switch may be faulty or starved of signal due to a clogged sensing tube.

– For jet pumps: Verify prime. Air leaks on the suction line or a faulty foot valve let water drain back, breaking prime.

– For submersible pumps: If the control box (where present) tests ok, measure resistance across motor leads; readings far from expected tables suggest motor or cable issues. Specialized insulation resistance tests require proper equipment and training—defer if uncertain.

Low pressure or low flow often traces to restriction. A clogged sediment filter, partially closed valve, or fouled screen can reduce throughput. If filters are clean and valves open, consider the well’s static and dynamic levels—drawdown may be exposing the pump intake, causing air ingestion. Intermittent air spurts point to falling water levels or a pinhole leak on the drop pipe. Observe the pressure pattern: a slow climb to cut-out indicates normal demand; a sluggish climb that never reaches target can indicate impeller wear or significant restriction downstream.

Short cycling—rapid on/off bursts—usually means the pressure tank’s air side is off-spec or the diaphragm/bladder has failed. With power off and system drained, verify the tank’s air charge. If proper charge doesn’t stabilize cycling, hunt for leaks: fixtures, outdoor spigots, or buried yard lines can quietly bleed pressure. Adjusting the switch is a fine-tuning job; keep the cut-in/cut-out spread adequate (e.g., 20 psi) to give the pump a reasonable run time. If you reduce the spread too much, you increase starts per hour and shorten motor life.

Two diagnostic contrasts help: Electrical faults tend to be binary—on or off—while hydraulic faults show gradients—reduced flow, noisy operation, or pressure that never quite reaches setpoint. Also, surface jet systems expose issues audibly and visually (you can see leaks, hear cavitation), whereas submersible setups demand inference via gauges, current draw, and switch behavior. Document findings as you go. A few measured values—gauge pressure at symptoms, amperage during run, filter condition, time to recover from cut-in to cut-out—turn a hunch into a clear next step.

Installation: Planning, Sizing, and Doing It Right

A thoughtful installation begins long before tools hit the ground. Sizing the pump to the job prevents both undersupply and premature failure. First, estimate household demand. Most single-family homes operate well with 5–12 gallons per minute (GPM), depending on fixtures, irrigation, and simultaneous use. Next, calculate total dynamic head (TDH): static lift from water level to destination, friction losses in piping and fittings, and the pressure requirement at the tank—commonly 30–50 or 40–60 psi (add ~2.31 feet of head per psi). This composite number guides pump selection more reliably than horsepower alone.

Well depth and yield shape the design. For submersible systems, position the intake several feet above the well bottom to avoid sediment. Use appropriately rated drop pipe—polyethylene for flexibility and corrosion resistance, or steel for rigidity—plus a torque arrestor and safety rope sized for the pump’s weight. Install a pitless adapter for freeze-proof, sanitary lateral exit below the frost line. All electrical splices should be watertight with heat-shrink connections designed for submersion, and cable should be secured at intervals to control movement during start-up torque. At the well head, a sanitary seal and intact cap are non-negotiable to keep debris, insects, and surface water out of the casing.

Inside, match the pressure tank to the pump’s output so run times are healthy. A useful rule of thumb is to aim for at least one minute of runtime per cycle at peak flow—if your pump delivers 10 GPM at system pressure, target around 10 gallons of drawdown. Note that a tank’s total volume is larger than its drawdown; for example, to achieve roughly 10 gallons of drawdown at 40/60 psi, you may need a tank in the 40–60 gallon total volume range depending on bladder design. Set the tank’s precharge to 2 psi below the switch’s cut-in pressure for stable cycling. Keep the pressure switch, gauge, and isolation valves accessible for future service.

Two installation comparisons are helpful. Submersible pumps offer quiet operation and efficient lift for deeper wells, while shallow-well jet pumps simplify maintenance where water levels stay within suction limits. For piping, larger diameters reduce friction loss and energy use, but require more space and cost; sizing to keep velocity within common guidelines (often around 5 ft/s or less for cold water) balances efficiency and practicality. Finally, confirm local codes and permitting requirements, especially for electrical work and wellhead sanitation. When in doubt, involve licensed professionals for wiring, deep-well retrievals, and water quality treatment integration—safety and compliance pay off for decades.

Conclusion and Next Steps: Reliable Water, Fewer Surprises

Reliability is a habit. The combination of routine care, clear diagnostics, and thoughtful installation planning keeps water steady, energy use reasonable, and equipment stress low. Treat your system like a small infrastructure project—because it is. A few repeatable practices form the backbone:

– Keep a simple log with dates, pressure readings, filter changes, and notable sounds or behavior.

– Test tank precharge annually and replace worn components before they fail at inconvenient times.

– Track amperage and pressure during a test run twice a year; numbers tell a story long before symptoms appear.

– Inspect the well cap and surrounding grade so surface water and pests stay out.

For performance and efficiency, consider incremental upgrades rather than sweeping changes. If irrigation causes pressure dips, a larger tank or a constant-pressure control strategy can smooth demand. If water shows sediment after storms, add a spin-down or cartridge filter upstream of finer treatment to protect fixtures and appliances. For households that expanded over time, revisit pump sizing: extra bathrooms or outdoor use may justify a recalculation of TDH and target flow. When drought lowers water levels, a service visit to check pump depth and protective controls can prevent dry-running damage.

Know your boundaries. Comfortable DIYers can handle tasks like checking precharge, replacing filters, cleaning switch contacts, or swapping gauges. Call a licensed professional for deep-well retrievals, electrical insulation testing, pressure vessel replacements, persistent contamination, or any job requiring permits. Typical ownership costs vary by region, but many routine items—gauges, cartridges, switch points—are modest compared to emergency replacements. The payoff is steady, clean water and a calmer relationship with your home’s most essential system.

If you’ve read this far, you already have the framework: maintain on a schedule, troubleshoot with evidence, and install with a plan. Combine that with a safe respect for electricity and pressure, and your well pump will serve quietly in the background—exactly where reliable systems belong.